A Story of NCHU Library

A Story of NCHU Library– The Amazing Life of a Table Named Vigo

Dedicated to NCHU Library staff who had been through the 921 Earthquake together

The Meniki Tree

My name is Vigo. I am here to tell you a story about a table and a library. My life began with a tiny seed of Meniki (Taiwanese red cypress). Carried by wind, one day I dropped to the ground near a giant fellow downed by a bolt in a stormy evening. With the open space left by the fallen giant, I was shined by sunlight and soon a sprout burst out. This was 1796, the year the aging Emperor Chien-Lung (乾隆) passed the crown to his son Chia-Ching (嘉慶). I found myself taking root in a deep valley of Mountain So-Chen (守城大山) shrouded by mist and cloud all year round. The mountain, a century and half later, became part of Huei-Sun Forest (惠蓀林場), an affiliation of Chun-Hsing Univerversity (中興大學). Two hundred years ago, Mountain So-Chen remained as a virgin forest with lush-green and tall conifers. It was so quiet that one could only hear wind whispering and streams running. What I enjoyed most was moisture and cool air brought in by east wind from the Pacific Ocean. I soaked in mountain dew in the morning and bathed in brief golden sun at noon. I still remember vividly the tranquility and languor I had before. Life like this went on for 150 years. I became a towering tree with shining scaly leaves and thick fibrous brown bark, 30 meters high and 150 centimeters across. I was a healthy Meniki tree standing tall in a valley of Mountain So-Chen. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1. Vigo – the towering Meniki tree.

Figure 1. Vigo – the towering Meniki tree.But my peaceful life soon came to an end. In an early spring morning of 1954, a group of loggers with chainsaws appeared on the edge of the forest. A brutal clear-cut began without mercy. All Meniki trees in the valley were felled and topped at the stump. No one was spared. We were loaded on trucks and transported to a sawmill called Taiwood (台木公司) on Nan-Men Road (南門路) in Taichung city. (Fig. 2)

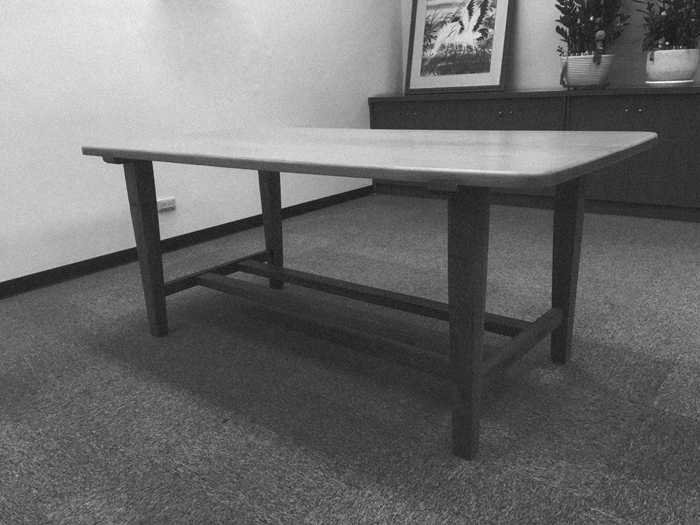

Firstly, I was sliced into thick, flat planks. After that, I was trimmed squarely and became a board of 180cm long, 90cm wide and 5cm thick. Then four legs were added down below. They were connected by two linkage bars as foot rest. (Fig. 3) Until now, this remains the most distinguished feature of mine. I began to take shape of a table. Finally, I was polished and painted with clear, glossy lacquer. I was made a glittering solid-wood study table.

Figure 2. Site of past Taiwood (台木公司) on Nan-Men Road (南門路). Now it becomes an empty lot where many mango trees grow.

Figure 2. Site of past Taiwood (台木公司) on Nan-Men Road (南門路). Now it becomes an empty lot where many mango trees grow. Figure 3. Vigo just finished – the study table with 2-bar linkage as foot rest. The top board is a single piece of solid-wood Meniki. The count of year rings exceeds 160.

Figure 3. Vigo just finished – the study table with 2-bar linkage as foot rest. The top board is a single piece of solid-wood Meniki. The count of year rings exceeds 160.The Young Provincial College

One day, in a short drive I was shipped to a two-floor building. It was a newly completed library of Taiwan Provincial College of Agriculture (臺灣省立農學院). (Fig. 4)

In fact, this college was just one block away from Taiwood. It was worth mentioning that the library was the first and tallest reinforced-concrete building on campus at the time. Along with other tables, I was moved and placed in a study room on the 2nd floor. From then on, I served as a table with four chairs for students to study and do homework before and after class. (Fig. 5)

In 1954, the provincial college had a rather small campus, compared with the present one, spanning east-to-west from Kuo-Guan Road (國光路) to the famous Palm Road (椰林路) and north-to-south from Hsin-Da Road (興大路) to Zhon-Min South Road (忠明南路). Kuo-Guan Road (國光路) and Zhon-Min South Road (忠明南路) actually were not developed yet. The college was surrounded by immense rice paddies, vegetable fields and fish ponds. Later on, some place there became the site of the present library. (Fig. 6)

Buildings and classrooms scattered mainly along Palm Road. The library faced eastward and was located in the southwestern corner of Palm Road and Da-Shuei Road (大學路). This is exactly the location of the Science Building at present. Across Palm Road was my obstreperous neighbor, track field, where students played sports. (Fig. 7) Now stands the Building of Civil and Environment Engineering.

Figure 4. Library of Provincial College of Agriculture in 1954. Palm trees were just planted.

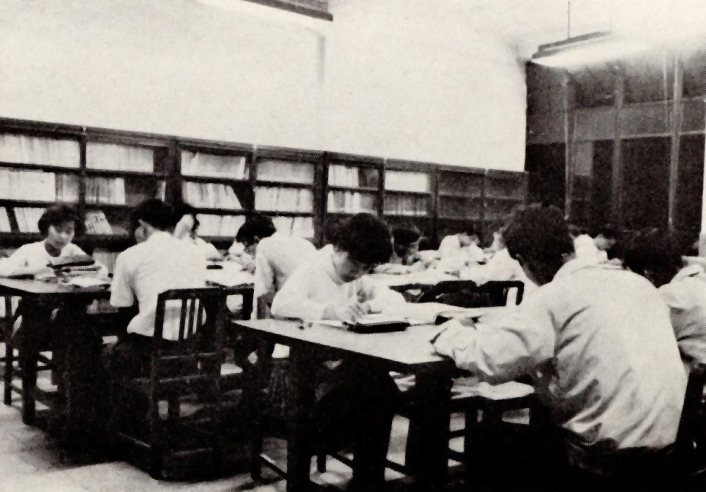

Figure 4. Library of Provincial College of Agriculture in 1954. Palm trees were just planted. Figure 5. Diligent students studying in library in 1950s. Each table typically seated four students.

Figure 5. Diligent students studying in library in 1950s. Each table typically seated four students. Figure 6. Rice paddy in 1950s around site of the current NCHU library.

Figure 6. Rice paddy in 1950s around site of the current NCHU library. Figure 7. Track field in foreground and library in background. Years later they became neighbors again in the southwestern campus.

Figure 7. Track field in foreground and library in background. Years later they became neighbors again in the southwestern campus.1954年,相較於現今,省立農學院的校園範圍小了很多。由東到西,是介於國光路到精勤路間,由北至南,則是從興大路到忠明南路。當時的國光路和忠明南路皆尚未開發完成。農學院四周環繞著大片的稻田、菜園和魚池。其後,那片土地的某個區塊,就座落了如今的圖書館(圖6)。

當時的建築物和教室主要是沿著椰林路分布,圖書館面朝東,位於椰林路和大學路的西南角,即今日理學大樓的位址。穿越椰林路後,會看到我喧鬧的鄰居-田徑場-學生們進行各種運動的地方。現今則是土木環工大樓的所在地(圖7)。

1950年代時期,省立農學院的所有教師成員有113位,5個系的學生總數約1000人。雖然那時的物質生活較為匱乏,學生們的學習精神卻令人欽佩。他們求知若渴並認真學習。為了能優先搶得座位,總是一大早在圖書館未開館前便於門口排隊,館內320個席次幾乎天天滿座;每到夜晚,圖書館即成為校園內最明亮的大樓(圖8)。

1960年代早期,剛好是戰後嬰兒潮世代要進入大學的年齡。1961年,省立農學院獲准轉制為3個學院的省立大學,首次正式出現「中興大學」這個名稱。興大透過幾次的土地徵收,將過去是稻田和魚池的土地納入,開始朝西擴大了校園版圖。從那時起,學校迅速開發並往外擴展。在主校區內的13個系所,學生註冊人數很快就超過了1700人。為了滿足日益增長的空間需求,在原圖書館大樓北邊增建了一棟三層樓附屬建築物,與原有建物呈現L形排列(圖9)。所有木製傢俱都被翻修和上漆,在新建築開館當天,我穿戴上深棕色的亮彩新衣來歡迎學生們。

Figure 8. Library in the evening – the brightest building on campus in 1950s.

Figure 8. Library in the evening – the brightest building on campus in 1950s. Figure 9. Three-floor annex on the north side of the original library.

Figure 9. Three-floor annex on the north side of the original library.The Bowl and Closet

Explosion of student enrollments inexorably led to the need of a new, spacious library. Land on the south shore of Chung-Hsin Lake (中興湖) was chosen as the construction site. The new library building was completed in 1980. And it quickly became the landmark of the university. The building was a complex comprising three sections: a four-floor, bowl-shaped structure for study rooms in the east, a tall rectangular tower for book storage in the west, and a connection structure in between. (Fig. 10)This unique feature in outlook soon lent the building to a nickname for Bowl and Water Closet. Not reverent but amiable in a sense. The bowl provided a capacity of 1000 seats, solving the long-term space problem of the library.The tower was a huge concrete structure in exterior that enclosed a stack of 7 floors built inside independently, each with steel plates juxtaposed in rows. An upper floor was stacked on the lower one with steel columns for the upright support, floor by floor. This fatal design, 19 years later, contributed to the disastrous destruction of itself in the 921 earthquake. Shortly we all moved into the new building, and I still served as a study table. One day many long tables arrived. They were new study tables in place of us. Alas! My miserable life began from then on. These tables were made of plywood with two flat supports down under. (Fig. 11) They were painted light tan and had a hard vinyl table top. These tables came with chairs that looked odd. Each chair was made of a single piece of thick plywood bent in an “ㄣ” (pronounced as an) shape. They were really one of the kind! However, no one recognized me – beneath the thick brown paint, I was a genuine solid-wood Meniki table – and I was moved down to the basement. This place was a big garage, and I became a stock table there.

Figure 10. The majestic Bowl and Closet before 921 Earthquake. But on the day of the earthquake, water towers on roof were toppled. Water spilled out and gushed down through cracks on sidewalls like waterfall. The basement instantly became a swimming pool.

Figure 10. The majestic Bowl and Closet before 921 Earthquake. But on the day of the earthquake, water towers on roof were toppled. Water spilled out and gushed down through cracks on sidewalls like waterfall. The basement instantly became a swimming pool. Figure 11. Plywood tables and chairs in the Bowl and Closet. These tables and chairs are extremely sturdy. Their toughness was tested and proved 100% quake-resistance.

Figure 11. Plywood tables and chairs in the Bowl and Closet. These tables and chairs are extremely sturdy. Their toughness was tested and proved 100% quake-resistance.In 1971, the university turned into a national university, and it reached a size of 3172 students and 684 faculty members in 23 departments. As time went by, library staff piled stuff of all kinds upon me: outdated newspaper, broken chairs, even wok and stove, anything you can think of. At one time, believe it or not, I became home and playground of a cat family with kittens hopping around. In the late spring of 1999, the library was infested with flea carried in most likely by these stray cats. Notice that, my fellow, flea also climbs stairs. The curator ferreted out and tracked all the way down to the basement. By accident he saw me buried overwhelmingly by the stuff like a hill. After scratching off some paint and smelling the wood, he immediately found my identity: a Meniki table. I was extricated from a miserable life of approximately 18 years. Soon I was shipped to a workshop where a carpenter scraped off the worn-out dark paint. I was polished and painted with clear, glossy lacquer again. I regained the elegant, radiant mien I had 40 years ago. One day I overheard a plan of putting me in a corner of the bowl for exhibition as an antique. I was so delighted that I could hardly wait for that moment to come.

The Quake

On September 21 in 1999, an earthquake of magnitude 7.3 hit hard in the central Taiwan area after midnight. This changed the course of my life again. The library itself suffered severe damage like many other buildings on campus. In the morning, library staff gathered together around the main entrance, waiting for assignment on cleaning up the mess. (Fig. 12)

All of a sudden, an aftershock of magnitude 6.8 struck. The earth initially shook up and down, then side to side in various directions. Jolts lasted for about 5 minutes. Staff members were shocked and ran wild to take cover. They witnessed two spectacular but terrifying scenes they never saw before. The three structures, especially the tower and the tallest, swayed violently left and right and bumped each other repeatedly with horrible cracking sound. Debris started to fall. This was because the three structures – the tower and the bowl as well as the middle section – were all at different heights. When the earth started to shake, the three structures swung at different paces, and they furiously rammed each other with tremendous impact on sidewalls. Worst of all, inside the tower,

Figure 12. Librarians awaiting at front door right before aftershock of magnitude 6.8. Minutes later the aftershock struck. Debris fell down like shower from the building behind them.

Figure 12. Librarians awaiting at front door right before aftershock of magnitude 6.8. Minutes later the aftershock struck. Debris fell down like shower from the building behind them. Figure 13. Librarians cleaning up the mess. Offices of all units were moved to the ground floor of the Bowl. It suffered the least damage during the earthquake.

Figure 13. Librarians cleaning up the mess. Offices of all units were moved to the ground floor of the Bowl. It suffered the least damage during the earthquake. Figure 14. Ceiling on the 4th floor dropped and littered as if being bombed. Since then it was closed and never open again.

Figure 14. Ceiling on the 4th floor dropped and littered as if being bombed. Since then it was closed and never open again. Figure 15. Pillar cross cracked. The crack was so deep that one could almost see through it. Cement was fragmented, and it could be easily peeled off.

Figure 15. Pillar cross cracked. The crack was so deep that one could almost see through it. Cement was fragmented, and it could be easily peeled off.the stack of steel-plate floors loading with hefty books on shelves wobbled like colossal jello. This exacerbated the swing of the tower. The second scene was that water in Chung-Hsin Lake was excited back and forth, and in a few seconds long waves formed and swept ashore. Throughout the day, tremors continued to occur but decreased in magnitude and frequency. By dawn on the next day, it began to calm down. Library staff showed up at eight o’clock sharp as usual. No one was absent. They entered the building to remove debris and sort things out. (Fig. 13) They found walls broken, ceiling dropped and pillars cracked. (Figs. 14&15) The library looked like a ruin. To their surprise, the main structure of the bowl remained intact. But the tower was completely destroyed. All the pillars were cross cracked at the bottom. Fissures appeared in zigzags all over the concrete walls. As for me, luckily I stayed in Curator’s office that night and survived without even a single scratch.

The Rebuild and Reunion

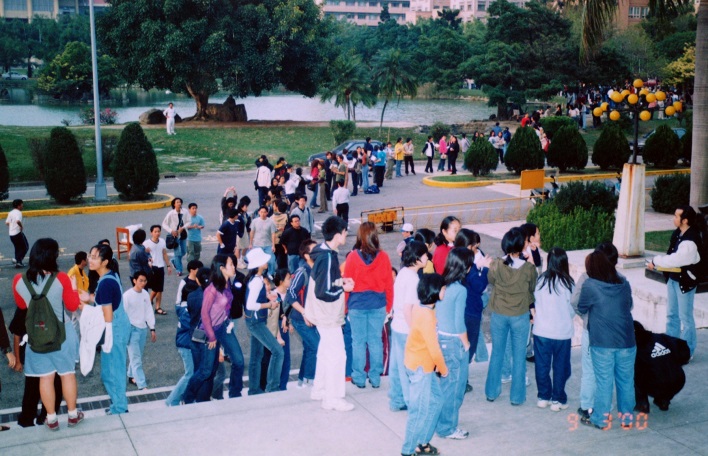

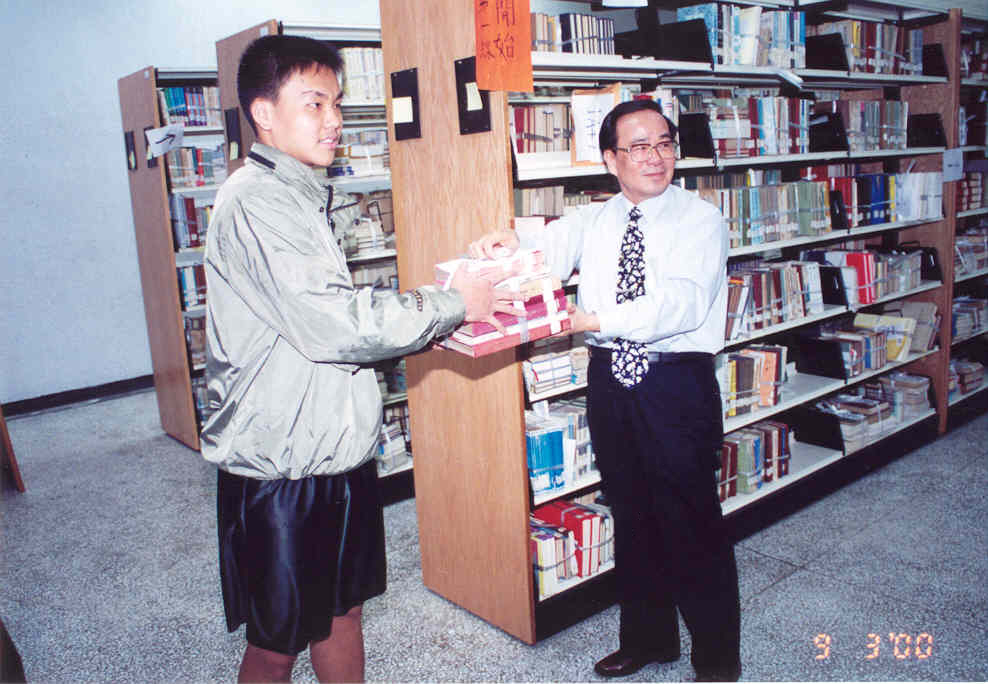

Waiting in no time, the university launched a series of restoration acts. Administrative and academic activities resumed. Damaged buildings started to repair. Library staff temporarily moved to the bowl. In just a few days, all units of the library began to function normally. However, two of the three structures, except the bowl, were seriously damaged. The university president ultimately decided to rebuild the library. Reconstruction of the library began with evacuation of books and materials to five different locations around campus. Among the events of evacuation is the notable “man belt” taking place on March 9, 2000. Approximately 1500 volunteers of students, faculty and staff were organized. They lined up in two lanes, relaying books from the ruined library to the Huei-Sun Auditorium (惠蓀堂). (Fig. 16) After that, one day the curator left and assumed a different position somewhere else. I did not see him since then. I was moved to the 1st floor in the Agronomy Building (農藝系館) as a temporary branch library. (Fig. 17) It was a dark, humid place surrounded by thick vegetation. The building received little sun even at noon. Lights were too dim to read by. There I became a study table again, but no one ever paid attention to me in such a gloomy

Figure 16-1. Man belt stretching from the ruined library to Huei-Sun Auditorium. Volunteers included mainly students, staff and faculty.

Figure 16-1. Man belt stretching from the ruined library to Huei-Sun Auditorium. Volunteers included mainly students, staff and faculty. Figure 16-2. President Chen-Chang Lee passing the first bundle. He led the university through the toughest time of recovery while morale was at the lowest level.

Figure 16-2. President Chen-Chang Lee passing the first bundle. He led the university through the toughest time of recovery while morale was at the lowest level. Figure 17. Temporary branch library at Agronomy Building. Vigo stayed there for about 5 years before it moved back to the new library.

Figure 17. Temporary branch library at Agronomy Building. Vigo stayed there for about 5 years before it moved back to the new library. Figure 18. NCHU library luminescent as dusk falls. The hardship of Vigo’s past faded away just like sunset.

Figure 18. NCHU library luminescent as dusk falls. The hardship of Vigo’s past faded away just like sunset.Six years elapsed quickly, and the new library building, the present one, was finally completed in 2005. This is a seven-floor structure with lots of wide glass windows. (Fig. 18)

It has a space three times that of the Bowl and Closet, providing 1500 seats and many trendy facilities. (Figs 19&20) A week before the grand opening, I was moved back to the new building. I eagerly anticipated to get in place and to serve as a study table again. But I saw an army of brand-new, stylish tables already upholding every corner of the library, from the bottom floor to the top floor.

There is no room for me. I ended up with seating in a remote aisle somewhere on the 4th floor. From then on I became an art workbench. Another 12 years flew by. I bore countless cuts, scratches, and paste patches on my back. One day, the long-gone curator returned, and he spotted me standing sadly in the dark aisle. The course of my life was changed one more time. I was renovated by the same carpenter I encountered 18 years ago. After being polished and painted, I become a luminous, radiant table but only for exhibition this time. (Fig. 21) My dear fellow! Come visit me in the designated exhibition area on the 4th floor of the library. Let me tell you more stories about the library and, of course, myself – once a giant Meniki tree, a study table, a stock table, an art workbench, now an exhibition table and a veteran.

Figure 19. Study room with fashionable furniture and digital facilities.

Figure 19. Study room with fashionable furniture and digital facilities. Figure 20. Lazy-bone Hollow where students in reading postures at their disposal. This is such a cozy place that students easily fall asleep in the afternoon. They are in sharp contrast to the students shown in Figure 5.

Figure 20. Lazy-bone Hollow where students in reading postures at their disposal. This is such a cozy place that students easily fall asleep in the afternoon. They are in sharp contrast to the students shown in Figure 5. Figure 21. Vigo – an exhibition table now. Poster on the wall shows 2 students discussing on Vigo about 50 years ago. Notice the wood attached to the short bar between the two legs in the left. The short bar was actually broken for unknown reasons. It is supported bottom-up by the wood. This marks the deep wound Vigo suffered in the past.

Figure 21. Vigo – an exhibition table now. Poster on the wall shows 2 students discussing on Vigo about 50 years ago. Notice the wood attached to the short bar between the two legs in the left. The short bar was actually broken for unknown reasons. It is supported bottom-up by the wood. This marks the deep wound Vigo suffered in the past.APPENDIX – A Brief History of NCHU Library before Provincial College

The NCHU history can be traced back to the Japanese-occupied era from 1919 to 1945. In the beginning, the colonial government in Taiwan founded Taiwan Gubernatorial High School of Agriculture and Forestry (臺灣總督府農林專門學校) in Taipei. This was the predecessor of the NCHU. The Taichung campus in Chiaozi-Tou (橋子頭) was developed in 1943. The school was moved to the new campus in October of the year. A library was formally established. It was located in the house next to the Little Auditorium (小禮堂) at the end of Palm Road. (Fig. A-1) It dwelled on a lot of 590 square meters. This was the origin of the NCHU library. In 1945, Japanese left and the school was renamed Taiwan Provincial Taichung Technical Institute of Agriculture (臺灣省立臺中農業專科學校). Next year the institute changed its name to Taiwan Provincial College of Agriculture (臺灣省立農學院). Two more library branches were installed at Department of Agricultural Economics and Department of Forestry, respectively. At that time, it collected 27,000 volumes mainly on agriculture and other related areas.

Figure A-1. First library in NCHU history – house at right of Little Auditorium. Both were ruined by the notorious 921 earthquake. At present, the Little Auditorium is actually a replica enlarged by 20%. The house was simply demolished and removed.

Figure A-1. First library in NCHU history – house at right of Little Auditorium. Both were ruined by the notorious 921 earthquake. At present, the Little Auditorium is actually a replica enlarged by 20%. The house was simply demolished and removed.國立中興大學圖書館 Last updated 2024-02-27 14:02:31

- Home page

- About

- Overview

- A Story of NCHU Library

- A Story of NCHU Library